Reliability: A model of trust and sustainable platform operations

- Reliability is key objective, and many organizations march towards as many 9s as possible, but struggle to effectively align development budgets

- Partnership in reliability story requires additional 'levers of reverse demand' betweens operational, development, and business teams; this tells the business when it is time to change focus from feature development and support to reliability enhancement work

- There are important distinctions between SLA, SLO, and SLI (Server Level Agreements, Objectives, and Indicators)

- The first and great commandment of Reliability Engineering is to establish and maintain error budgets, which are estimations of imperfections in a platform against the measured time to resolve

Preface

Delivering a platform in an IT organization involves meeting a set of goals that must be pursued simultaneously:

- Delivering business value on a platform (through both features and outcomes)

- Supporting users

- Eliminating platform risks (such as downtime, security gaps, latency and various data issues)

Each of these goals involve trade-offs in time and focus, and often involve agreements between the teams responsible for their delivery. Failure to achieve these goals will put a platform in a downward spiral of lost confidence, project delays, and conflict as additional effort is put into place to mitigate risk.

This document is written to highlight the common vector by which each of these goals are measured – Reliability – and to give quantifiable methods to achieve this with our business teams. This document is also intended to bring clarity to factors that lead to a "death spiral" and how this can be avoided in an IT organization.

The end of this document lists action steps that will assist platform operators, developers and project managers in aligning with business teams. It is worth highlighting upfront that these steps will be unlikely to succeed by edict, but rather by selecting teams willing to put in an initial effort (which doesn’t have to be a lot). Even a starting point here will provide value for future efforts as we outline success criteria. These outcomes will direct further efforts and provide an opportunity to disseminate knowledge to other teams, bringing them into a sustainable process.

This article draws from my own experience and that of teams I have worked with during the last 8 years in IT after transitioning from a backend engineering role on a large SaaS product. This also draws from luminaries in platform delivery and reliability engineering, such as Ben Treynor, Dave Resnin, and Henry Robertson (VP, Director, and Sr. Manager, respectively) from Google, as well as authors of the SRE Handbook: Chris Jones, John Wilkes, and Niall Murphy; and last but not least, Dan Neff, Principal Architect at Adobe.

Reliability is Key

Imagine that you have a set of knobs that can be turned, each one representing different characteristics of a platform such as reliability, security, features, scalability, UI. By turning all knobs to the highest value, you now have maximum reliability and security, a ton of sweet features, scalability for ages and a drop dead gorgeous and functional UI. Now imagine that you are told that one can remain high, while the rest need to drop down to 10%. Which one will you choose? Conversely, if you could keep all high, but had to choose one that would be turned off, is there one that you would avoid at all costs?

Yes, it is true that lacking security is bad, same with lacking features. There is no denying that great value can and should be attributed to each of these characteristics, as well as several others not listed here. The point is that there is one that will almost single handedly guarantee failure for a platform if absent: reliability.

If this is the case, we must certainly want to plan for it. There are many guidelines that exist to date; but surprisingly when it comes to the ability to inject reliability into a platform in a quantifiable manner, there are remarkably few resources available in how this should happen. Take this amusing quote by Dave Resnin, director of Google SRE: "Reliability is the most important feature. It is also not on any PRD. This means up to now we are mostly engineering our platforms by luck."

But why emphasize reliability at all? Certainly we can give a nod and a glance, check off a box and then get back to the more important (and fun) work of features and scalability, right?

It turns out that the reliability picture makes the most sense when one looks at the nature of how products work. Note the distinct use of the term 'product' here aside from 'platform'. The utility of a single product is magnified when it is able to leverage the user base and functionality of complementary products. This means that according to some cost/benefit curve, integrations will inevitably be created between them, whether or not APIs were created for this purpose. Another quote by Dave Resnin is "All critical products become platforms. Therefore, the total stability of the resulting platform is the reliability multiplied across the integrated landscape of these products/platforms."

Furthermore, consider how this reliability changes over the course of a platform's lifetime. Whereas a product supported by IT is easily configurable during the early rollout phase, as it matures to platform status this will change to be highly dependent on the needs of the user base. This is because at the broad platform level, these choices now have at least as much impact on the reliability they experience, and probably more.

Reliability is a Partnership

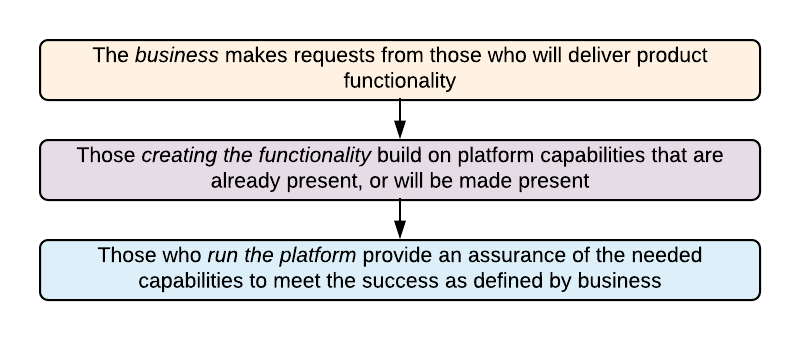

To provide reliability it is important to understand how this exists within a company between different stakeholders. Typically, the relationship between members representing 'the business', 'the delivery', and 'the platform' has natural asymmetry. This is illustrated in the image and uses arrows to show the direction of demand.

Let's look at these relationships by how the incentives are formed. We'll take an over-simplified analogy to describe this. Imagine a game of blackjack or poker, where capabilities are represented by a deck of cards. These are dealt 'on demand' to fulfill requests of the players sitting upstream. In this analogy, the platform team holds the entire deck of cards and reactively/proactively deals. The game is the platform team's to lose. The trick is that the rules to win the game are not determined downstream, but by the business. Because of this, there is naturally a heavy trust bottom-to-top, and preferably more than a surface understanding of what the business will call a winning hand.

This simple analogy is not presented to discount a top down incentive model. Incentives exist and are important to delivering value. It is also prudent for the platform to align with the business for other reasons than to simply 'enable delivery' since, in the short term, this alignment is what keeps the platform viable. Following too closely to this, however, is what creates disincentives for solving real problems, as looking good to the business will trump genuine innovation and managing overload.

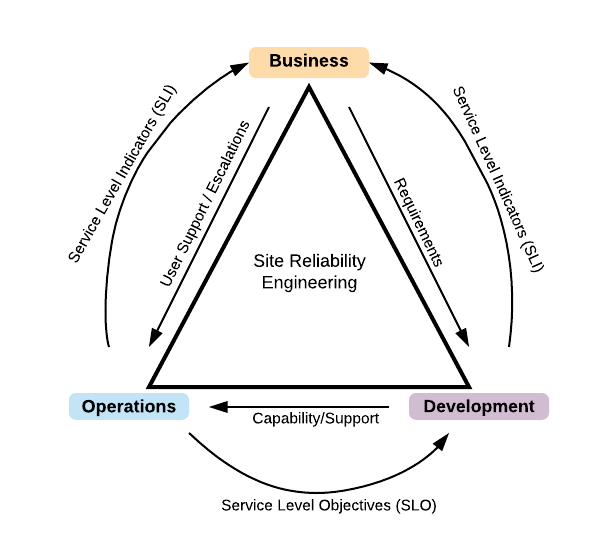

An evolved view, or a longer term view, means that teams will want to organize and optimize for successful outcomes at all levels (i.e. 'all players can play for a winning hand'). Thus, a model for partnership requires a different view such as the one below, described by Henry Robertson:

The primary difference in this model is that there are symmetric 'levers' in the relationship that can be pulled, which allow demands to be made in both directions.

These lines are drawn along implicit or explicit agreement from all parties, which means even though the word 'demand' is used, it really is more of a partnership agreement. The terms SLI/SLO will be explained later in more detail. For now, simply consider SLI a measure of indicators of customer happiness or unhappiness, and SLO a measure of metrics in the system that affect SLI.

This, along with taking guidance from the following sections on “setting proper expectations” and “adhering to models that create trust”, will enable teams to be on equal footing. When teams have measurable terms for success and an agreement to what level of service is provided, decisions on how these teams should be staffed, and prioritization of effort can be strategically driven and justified to other parties.

Dan Neff summarizes the work in operations with such a model: "I am happy to do what it takes to help the business get their data for a critical delivery, since I know that while I am protecting the delivery on the technical side, those that need this report are justifying my effort to the business and buffering for my work on the other end."

Setting Proper Expectations

There are two statements that bear repetition until we understand the wide implications: 1) We can never expect perfection as humans are imperfect. 2) Making gestures that we are 'aiming for perfection', or setting goals that require perfection are counter to human nature, and as noted by Dave Resnin: "will surely turn employees into liars".

Though this may seem to pull down aspirational desires, it helps to look at this from the standpoint of human behavior. How will an individual act when they inevitably fall short of unattainable expectations?

Rather we should use a more appropriate tactic. Consider arriving at proper expectations by answering this question: 'what imperfections are we willing to tolerate?' Just by approaching it from this angle, any engineer or operator can start with a list of what imperfections they know exist, which can be reviewed for costliness in terms of business revenue, user dissatisfaction, system correctness, etc. Already, this is more useful than setting an expectation that cannot be achieved, as the incentive is now to share, rather than to hide.

Given that a well-intentioned human error will likely be followed by another well-intentioned human error (hopefully of a different class), we should focus on eliminating a recurrence of the same errors and limit the blast radius of errors [Resnin]. This is also something that we can take into account with our systems of automation and remediation, as even they are enacted and based upon human skill, with reasoning based on the best data that could be gathered.

Adhering to Models that Create Trust

Before we get quantitative, it makes sense to highlight the qualitative aspects of the user to platform relationship. These subsections give more detail on how reliability and service provider functions cross the technology boundary1.

Recognizing business objectives and experiences on the platform

From the business side, there is a relationship that forms when users depend on a platform. When a bad experience happens, the users will implicitly blame the platform even if it was a wrong action on their part. This is because they are drawing on emotional memory2 not because they are bad people.

If we form the user population into two over-simplified clusters, we can call one the solution-seekers and the second the support-seekers:

Solution-seekers: On this end is the group that will seek corrective information and apply it with iterative effort to fix their poor experience. They are typically operating asynchronously from platform support persons.

Support-seekers: The other end is a group that will commonly have other interests or time constraints and will lean heavily on platform support to provide patch solutions on their behalf. In addition they often seek to work synchronously with platform support persons.

Support model tiers are created to triage these user clusters appropriately, and higher tiers are naturally removed from the immediate break-fix support. What this doesn't account for is the need to create invested users; it is a support model, after all. One opportunity to create this investment (or perhaps to simply avoid building resentment) is the understanding of the business objectives from the platform team. The empathetic exercise of this knowledge is a call to trust the decisions made on the platform, whether or not they directly speak to immediate business crises.

Building platforms with "invested" business partners

The operating model for a platform determines the expectations of its user base. It is important to note that the user perception of this model is just as important as its actual implementation. My personal experience is that an operating model that feels 'free' will be used in ways adverse to goals of reliability.

This is all that will be said here for the purposes of creating invested business partners, as the 'how' goes beyond the scope of this article. What is critical here is to maintain a set of practices that build a platform for solution seekers, and then to use this partnership with the business to establish metrics that are visible and lead to customer happiness and unhappiness (SLIs) and use this to direct focus into development or operational channels.

Service Level Agreements, Indicators, and Objectives

In order to provide for the assumption that a service will not be available 100%, there are several concepts to describe areas of focus with objective measures.

SLA (Service Level Agreement): This is a binding agreement between a service provider and its customers, and is typically tied to refunds or legal action when it is broken. This will not be widely discussed in this article since internally the SLOs will be built around avoiding an SLA breach. Also, team relationships will end up structured more around SLOs.

SLI (Service Level Indicator): As mentioned previously, these are measures of some aspect of the service that correlates with user happiness or unhappiness. An example would be a Netflix user pressing the 'play' button. A millisecond response, a multi-second response, and a failed response will all track with increasing levels of user unhappiness.

These indicators will naturally be tailored toward the type of service provided. While a user-facing system such as search or a video player may care most about availability, latency, and throughput in order to effectively serve users, a storage system may care more about latency, availability, and durability of data (i.e. is data there when I request it via read/write and can it be accessed on demand with reasonable performance?). Big data systems may care most about throughput and end-to-end latency (i.e. How much data is being processed and how long does it take to progress from ingestion to completion?). Another common SLI measure may be error rate on requests received.

When enforcing the time that is spent from platform operations and development, SLIs can be instrumental to keep focus on those items that are ultimately tied to user happiness.

SLO (Service Level Objective): These are target values or ranges for a service measured by an SLI. In going back to the Netflix example with pressing the 'play' button, there could be several systems that the user does not know or care about, that may be involved with a fast and successful attempt to start a video. By having the correct thresholds in different SLOs that are related to the SLI, there is now a specified target for performance. These can also be bounded for specific days of the week, and other factors that are unique to the platform service being targeted.

It is unrealistic and undesirable for SLOs to be met 100% of the time, as it has the detrimental effect of either reducing innovation and deployment, requiring overly conservative solutions, or both [Treynor]. Error budgets are intended to address this gap.

SLOs can—and should—be a major driver in prioritizing work for platform operators and product developers, because they reflect what users care about.

Once error budgets have been described, it will be seen that the activities of developers and platform operations will be able to shift with greater alignment between capability development, product features and reliability engineering work depending on the health of the platform as measured by SLIs and SLOs [Neff].

Error Budgets

Error budgets are a fundamental concept for measuring the gap between 100% reliability and a defined SLO. Using an example where an SLO is formed on 99.9% availability of a platform, this means that the error budget is 525.6 minutes per year.

From this budget, a team can take a list of imperfections on a platform and determine the amount of time an occurrence would take to detect and resolve. (See "Risk Stack Rank" tab at [https://goo.gl/bnsPj7] for a sample budget). Here are some fictitious examples of risks and estimated bad minute costs per year:

- Platform overload results in low or dropped requests during peak hour each day. Cost: 3559 minutes.

- A bad release takes the entire service down. Rollback is not tested. Cost: 507 minutes.

- Users report an outage before monitoring and alerting notifies the operator. Cost: 395 minutes.

Armed with a list of these imperfections, these can be grouped and affirmed with partner teams. The error budget determines that once an SLO is at risk or not met, development teams are enabled with time to address the risk prior to continuing feature development work. As such, these do not become a weapon of blame, but rather a call for partnership. To complete the thought of "shifting team alignments" brought up with SLOs, the operations and development teams will be able to jointly form a stronger co-development strategy as they have incentives to swing toward efforts for stronger reliability (and whatever other SLOs are formed), and for capability development that enables feature delivery.

An error budget also helps with prioritization – if there is a miss of an SLO last week, relevant bugs can be prioritized to help avoid SLO violations in future weeks.

Error budgets enable an IT organization to drive reliability with speed. As noted by Treynor and Resnin: Speed and reliability traditionally form an "X": a crossroad that both impede and are exclusive to efforts for the other. By working with error budgets, these become "co-linear" in that the measurement of reliability metrics can determine the speed of delivery, and vice-versa

Action Steps

The steps outlined here are just a start. The reason to start small is that there is tremendous benefit to simply beginning the process and outlining what is known. This can serve to inform teams and start the consensus building process. This works in an inverted fashion from a process such as GDPR, and buy in and value has to be seen quickly to justify the practices outlined in this article.

Steps:

- Pick a platform service of reasonable importance. It doesn’t work to pick a greenfield project that no users care about.

- Create a judicious selection of SLI measures that users of this platform will care about.

- List imperfections in the platform that would touch on this preliminary list of SLIs.

- Determine SLOs that will support achieving the positive user outcome of SLI metrics. a. This can be focused on a single area for now, such as Reliability discussed in this article. Other areas of focus can come later.

- Determine availability target for these SLOs, pick one, and create an error budget following this Google doc worksheet. Seek consensus with partner teams, to ensure SLIs are relevant to the business and SLOs can be supported by development. Use these to direct operational and development "spend".

References

1 Those familiar with DevOps principles will also recognize this as one of the pillars in reducing organizational silos.

2 For those curious on why emotional memory drives blame here, it is actually because of psychological bias which drives snap decisions when time or information is not available to perform objective reasoning.