Engineering a mindset of action and collaboration

"Running code wins!" You probably know what this looks like - imagine that one monolithic application or tangle of services which has been the most operationally demanding to you but that no one can seem to get rid of. The more you want to fix it, the more you fear that the time spent will end up in yet more long nights for you and your team supporting a new set of surprises that await. Or consider the release that was meant to be a prototype, but now is the shipping product. As a bonus the original engineers are gone, and the users are ramping up expectations. Either way, at some point you reflect and wonder "How did this mess even get released in the first place?" or "What is the quickest path away from all this thoughtless engineering and soul-crushing operational support?"

In this article I will explain not only why running code always wins, but why it is, in fact, pivotal to how we ought to behave as an engineer. "For shame!" you say. Before I dive into it, first let me take you back to my early days as a software engineer, back when my love of high-level computer language constructs led me to what I considered the peak of development practices at the time.

It was my first engineering gig out of college. Up until this point, I would consider my coding experience as ambitious, low pressure, and academic. Without the pressures of business as a forcing function for delivery, I had become a huge proponent of design patterns and found all the marvelous ways they could be used.

Avoiding large inheritence hierarchies? Favor composition! Hello Strategy pattern!

Family of similar objects with excessive concrete types? Time to save me Factory Method pattern!

It seemed that wherever I looked - boom - there was another hideous implementation to be reckoned with. Nothing like a little Gang-of-Four wizardry to make it beautiful and shiny! In my mind, I couldn't understand why anyone would settle for less.

This mindset carried me for a couple years, earned accolades from some, ire from others, and in hindsight, probably became too much of a Golden Hammer. This was also a business that actually burned CDs and shipped software to customers - which I realize is probably implicating myself, but seems appropriate to point out, since after moving to a new job I found myself in a fast paced SaaS world, and everything came crashing down on its head... Well, my head to be exact.

All of a sudden, it didn't matter if I spent an extra day organizing my file hierarchy traversal to use the visitor pattern. Why? Well because somebody sitting in the cubical next to me just whipped out his call to python os.walk() and it really didn't matter. At that point, all my Gang-of-Four inspired design patterns simply appeared to be overhead. Was it intrinsically wrong? Maybe not. Was it wrong in this environment?.. I say 'yes'.

Compounding this was my lack of perspective on how to arrive at decision points within the team so that we could see the type of feedback that told us if we were investing in the right vectors of work. Maybe a particular component needed more work for its critical place in the system, or maybe our database schema was about to morph in a non-backwards compatible way. And how could we do this in a way that didn't feel like a CS lecture or an affront to somebody's sense of what was 'right'?

Before I knew it, I was absorbed into this new culture where the status quo had become 'move fast and break things' - but then 'fix them really quick before the customer (or your manager) noticed'. Yikes!

Interestingly, some people appeared to do this well enough that they could continue, or even thrive(!) in this environment. That only further led the naive engineers among us to reconsider, 'Do we drop our best practice mindset and join in'? I for one realized that a 'fast-and-furious' approach is definitely one wherein I could not be successful and also, by my estimation, had a strong potential to worsen our engineering organization as a whole if it continued. Maybe you too are nodding your head because of similar instincts. If not, consider the last place you have worked that has attempted to codify this mentality by 'redefining' Agile development where tasks seemed to become a never ending cycle of sprint burndown (burnout?).

After seeing project after project in a SaaS organization turn from formal to frenzy over the course of a month, I realized the painful, but obvious lesson: "Running code wins, even if as a result we as a team of humans lose". Furthermore, I would also say in many cases this code would be considered "good enough".

So where did I go wrong?

Looking around, I realized that not all teammates were drowning in this type of environment. Yes, some would just keep their head down or know just the right time to disappear to the game room. But the group I found myself fascinated with were those team members that seemed to be succeeding in this environment: Collegues who where bright, no doubt, but even more important, had found a system that worked. I later adopted this system and found it actually could not only improve the quality/quantity of the 'code' that was produced, but also avoid many common traps; for example, the 'efficiency fallacy': One where you are so productive writing code that you don't realize you are solving the wrong problem, only to find course corrections bring increasingly higher risk, instability and suffering expectations later.

What is this system? Given in a talk several years ago by VP of GitHub Field Services, Matthew McCullough, it turns out it is as simple as ABCD :)

- Act

- Broadcast

- Condense

- Decide

I have found that this strategy helps work through unclear requirements, or impressions that code may overlap/interact with that of a collegue. It also helps to focus communication on the right material for the right audience, and to inhibit ego-centric development.

Let me explain what this has to do with "Running code wins".

I submit that the first principle of engineering is action but the only way to harness this for optimal outcomes is via decision. This is much different than a 'shoot first ask questions later' methodology, though. What we avoid in this framework is ‘analysis paralysis’. As a team we are motivated to create use cases and then crystalize those ideas into designs and prototypes. Not all prototypes become final products, but the learnings are extremely important to share, otherwise other team members will inevitably tread the ground again as similar problems are encountered.

Act – this is actually doing the early work. Break things into smaller parts and demonstrate ideas. Expect that not all work will be the final product, but enable ourselves to Fail Early. Tom Kelley (author and consultant at IDEO) puts it this way: “Fail often to succeed sooner”.

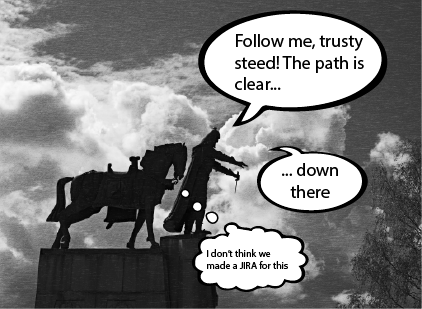

Broadcast – This is the idea that transparency and information sharing is critical. Others may learn and refine in ways we can’t foresee. Who do we broadcast to? According to Matthew McCullough, "target broadcasts to the people that need to act on message, but allow those who would have use of data to find it as well." We have many tools (JIRA, wikis, Slack, Git issues/pull requests) and should ensure we at least capture it and share it somewhere. Iteratively we develop the best patterns that work with our unique team dynamics.

Condense – When we need to reason about something, we need it summarized. This is a step where crafted communication, dashboards, and simplification are needed. It is also where we attune findings to the right audience, and often is the point to create "up leveled" communication. An Ops Chief at Github puts it bluntly: "Without some filtering, my world is 100% noise". This is where we establish ourselves individually and as a team as domain experts.

Decide – We decide iteratively. To me that is a powerful concept because it accepts the idea that we are all learning. "Big maneuvers result from many small ones". This is an area that requires discipline. One of my esteemed collegues, Steve Reiser has taught me a lot here with the concept of "Disagree and Commit", heakening back to his days at Intel. This comes into play when we are faced with multiple options and need to put maximum bandwidth behind one option and move forward. Here is an example I like: Imagine we have two hypothetical options, A and B. A is a good option which I present. B is a subjectively better option which you present. You will naturally want to argue against the merits of option B, which are not seen, and I may counter based on evidence, experience, or intution. Let's say we can't come to a decision. What do we do? Depending on the dynamics, we may have the luxury to prototype or further explore. But ultimately it is the same outcome, we need to decide and move forward. "Disagree and Commit" means that either I deprioritize or cease on option A and fully move together with you on option B, or otherwise you do the same and move with me on option A. There is no middle ground. Studies of organizational behavior find that this decision and commitment is key. Even taking a subpar option A with full commitment may turn it into a winning solution, while a luke warm embrace of option B could likewise turn a better option into a failure.

Some final thoughts: Without decision we can’t claim the benefits of our work. This is where we come together and work towards the shared goal. It isn’t about whose idea wins.. it’s about making it so our team wins.

If you find these insights useful, please let me know. There will be much more to come.